Olena Velychko, CFA, ESG Analyst at Nordea Asset Management

The growth of “fast fashion”, inexpensive clothing produced rapidly by mass-market retailers, has contributed to a doubling of global clothing production over the last 15 years, while at the same time the clothes’ utilization rate has decreased by 36%. This overconsumption of clothing is being driven by more collections and quicker turnaround as well as lower prices. The clothes lose their value quickly as new collections make them less fashionable and low prices, which have become the norm, make it easy for consumers to continuously replace clothing. The result is a buy-dispose cycle which is permeating the entire apparel industry with adverse consequences for workers.

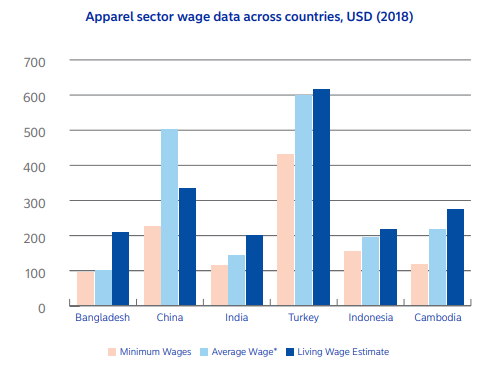

To understand the cycle, we must first consider how these clothes can be produced so cheaply.The selling prices do not reflect the true environmental and labour costs of production. Fast fashion companies in search of cheap markets source their labour from countries like Bangladesh, Myanmar and Ethiopia, some of which allow for lower trade tariffs on apparel due to their least developed country (LCD) status. In recent years, apparel companies have been increasingly sourcing labour from Turkey and Mexico due to their proximity to Europe and the US as the benefits of speed to market outweigh increased production costs.

Apparel companies that have achieved tremendous success in scale have been pushing prices down for the consumer. Since the apparel supply chain can be characterized as a “buyer’s market”, i.e. where supply exceeds demand and purchasers have an advantage over sellers in negotiations, the brand owners are in a good position to demand lower pricing and shorter lead time from their suppliers.

“The growth of “fast fashion”, inexpensive clothing produced rapidly by mass-market retailers, has contributed to a doubling of global clothing production over the last 15 years.”

Low-cost production environments present a particular social rights challenge: there is a large low-skilled labour supply in these markets, but fewer formal work opportunities, which means that workers have less bargaining power relative to factories regarding wages.

Legal minimum wages are not enough to live on in many of these markets: the minimum income necessary for a worker to meet basic needs for a family unit, including modest discretionary income, is below acceptable levels 2 . There are both social and economic reasons for apparel companies to address this.

The social reason is that minimum wages may not be sufficient to support advancement toward Sustainable Development Goals. Companies that barely meet the minimum wage threshold do not contribute to societal well-being or economic growth. The issue of fair wages is closely linked to many of the Sustainable Development. Goals outlined by the United Nations, especially goal number 1: No poverty, number 2: Zero hunger, and number 8: Decent work and economic growth.

The economic rationale to address wages in low cost production environments relates to the fact that minimum wages have been increasing and continue to increase in key sourcing countries, e.g. up by 82% in Cambodia and 51% in Bangladesh since 20133. Through our calculations in this paper, we show that while this is starting from

very low levels, it is material for both workers and companies with small margins in volume businesses like apparel. Hence, it needs to be addressed with foresight.

Consumer awareness of sustainable garment choices is increasing … yet both the consumer picture and the regulatory picture are incomplete.

The Boston Consulting Group’s most recent consumer sentiment survey4 found that not only is consumer awareness of the sustainability outcomes from fast fashion growing, but it has an impact on consumer purchasing decisions. More than a third of the respondents reported they already have switched from their preferred brand to another due to the brand’s impact on sustainability, and more than half said they expect that their next purchase will be affected by the brand’s responsibility practices.

Source: United Nations Sustainable Development Goals

Source: United Nations Sustainable Development Goals

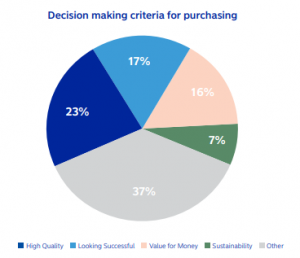

Yet the general consumer trends story is one of mixed messages. While consumers are increasingly interested in sustainability, fast fashion companies have also been very successful at finding buyers. For example, online retailer Boohoo has seen explosive growth in a market where customers are basing their decisions on price. Even though sustainability awareness is growing, it is not yet in top three most important criteria driving apparel purchase decisions, which are quality, look and price.

Source: Adapted by Responsible Investments, NAM based on data from the BCG survey

results published in the Global Fashion Agenda, Pulse of Fashion Industry (2019)

Although sustainability is not a top decision driver, it is still considered as a prerequisite for many consumers. While sustainability challenges connected to fast fashion are increasingly on regulators’ radar, we are not yet seeing them push beyond best practice to proactively advance sustainability causes within the industry. For example, in January 2019, the UK Parliament presented the results to an inquiry into the Sustainability of the Fashion Industry with quite strong conclusions that the current exploitative and environmentally damaging model for fast fashion must change. A list of specific recommendations was issued including a ban on incinerating or landfilling unsold items and reducing VAT on repair services. However, the UK government rejected the recommendations and has currently made no commitment to any specific policies 5.

Addressing the problem of persistently low wages

The heart of the matter is that the industry cannot wait for the consumers and regulators to press for ethical change but must itself step up with bolder solutions. One issue central to the problems proliferated by fast fashion is the industry’s failure to deliver living wages — this is also a key material ESG risk. The challenge around lower than living wages can cause supply chain upheaval: in Bangladesh there have been recent cases where worker protests have caused disruption to delivery times. In addition, very low wages negatively impact worker attrition and productivity. There is a business case for addressing low wages as this can put the stability of contracts and supply chains at risk.

Calculating materiality impact of reaching living wages

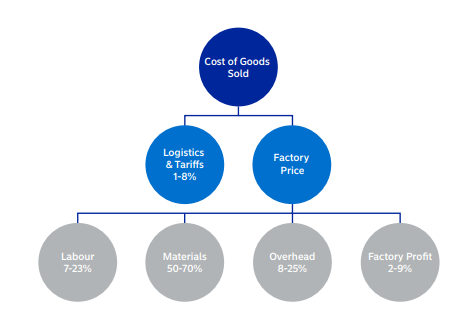

We estimated the impact increasing wages to the living wage level would have on factory prices (prices paid for ready-made garments to the manufacturers) to illustrate the business case. According to various estimates, labour costs share a range between 7% to 24% of prices paid to factories for ready-made products depending on

sourcing country 6. This is approximately 7-21% of cost of goods sold (COGS), or between 2.5-8% of the total cost structure. Average factory monthly wages were estimated using factory wage data (excluding overtime) supplied by H&M 7, the only large apparel company disclosing wage data in their supply chain. We used the most recent living wage estimates by Global Living Wage Coalition (which is using Anker method8) except for Turkey and Cambodia where we used WageIndicator.org for a typical family average of higher and lower estimates. These estimates and methods are rather conservative, compared to Asia Floor Wage, whose estimates are approximately 1.5-2 times higher.

Source: Adopted by Responsible Investments, NAM based on data from A Living Wage in Australia’s Clothing Supply Chain (2017) and Global Fashion Agenda (2017)

The largest gap between paid average wages and our living wages estimate is in Bangladesh where wages would need to double to meet living wage levels. Next is India, where depending on the region the wages would need to increase by 40%. In Indonesia and Cambodia, wages should increase by 15-25%. China is the only country in the study where wages paid to apparel factory workers are higher than living wage estimates (35% more).

The potential impact achieving living wages would have on prices paid to supplier factories depends heavily on the sourcing countries mix. For example, a company sourcing a third of its value chain from China, a third from Bangladesh and a third from a mix of India, Indonesia, Cambodia and Turkey, would face an increase of 3.5% to 9% in factory prices depending on the estimate of labour cost share. Companies that are not engaging with their suppliers on living wages and require only minimum wages, i.e. lowest minimum standards with the same mix of supplier countries, would face an increase of between 6% to 13% in factory prices.

When minimum wages or negotiated wages via collective bargaining agreements rise, they impact all buyers in the same way forcing even brands that have not committed to living wages to pay more to the factories. We see this as a factor that will put long-term pressure on the industry’s profit pool, particularly for companies that are not addressing the issue.

Source: Adapted by Responsible Investments, NAM based on data from H&M Sustainability report 2018, Living Wage in Australia’s Clothing Supply Chain (2017) and Global Fashion Agenda (2017)

How are companies already addressing the issue?

Some apparel companies are making efforts to address the living wage issue. Very few pay a Fairtrade premium for sourcing from certified factories (e.g. Patagonia) or pay a bonus to workers (e.g. Nudie Jeans). But these methods do not address the living wage problem in a structural and scalable way and are completely at the brand’s discretion.

Apparel industry ACT (Action, Collaboration, Transformation) maintains partnerships with 22 apparel companies and IndustriALL Global Union focuses on addressing the issue of living wages through industry-wide collective bargaining and fashion companies’ purchasing practices commitments that facilitate fair living wage payment by suppliers to workers. In addition to enabling living wages, industry level collective bargaining

agreements can reduce the risk of wage disputes between workers and suppliers and help to build more stable business environments. It is evident that fast fashion companies are facing tougher international competition as they strive to bring the best value for money to the market. That is whythey want a level playing field in terms of living wage commitments as they compete for suppliers. Cambodia is the first major country supplying the global apparel industry in which ACT is currently working on an industry-level collective bargaining agreement; it is expected to be finalized during 2019.

Companies have several options if they wish to address this issue. They may continue exploring further cheaper countries from which to source labour. However, the risks are very high, and it can take considerable investments and time, e.g. employee training and management of cultural conflicts 9 . They could also work to improve their own operational efficiency to absorb increasing costs.

Or they could focus their efforts on their suppliers by enacting factory level standards, enhancing working conditions, reducing staff turnover and improving employee health and motivation.

This would increase productivity and quality. They could also focus on increasing consumer awareness and preparing consumers to pay more for clothes. Finally, they could invest in R&D to replace costly and unsustainable elements of their supply chains and deliver products more efficiently to their markets 10.

Source:

Industry level living wages

What do we expect from sustainable brands?

There is a business case for apparel companies to address the increasingly material ESG risk of lower than living wages. Our perspective is that companies should address the risk by joining industry initiatives such as ACT and adjust purchasing practices to allow payment of living wages by their suppliers. We also believe it would benefit them to engage with suppliers on improving productivity and quality, especially in countries where factories struggle with providing value added products. It would be in the company’s interest to do this and provide a high level of transparency on the related strategy and progress.

Overall, responding to the challenge around lower than living wages in a sustainable way could help to improve the efficiency of their own operations as well as that of the supplier. These measures would increase product/service transparency towards their clients. As consumer demand for more sustainable apparel choices grows, efforts made to address the living wage question will not go unnoticed and could expedite companies’ process of adjusting their brand value proposition toward sustainability.

- Ellen McArthur Foundation, A new textiles economy: Redesigning fashion’s future (2017).

- Living wage is defined as the minimum income necessary for a worker to meet basic needs for himself/herself and his/her family, including some discretionary income. This should be earned during legal working hours limits (i.e. without overtime). See also The Universal Declaration of Human Rights (1948) that states (article 23.3): “Everyone who works has the right to just and favourable remuneration ensuring for himself and his family an existence worthy of human dignity, and supplemented, if necessary, by other means of social protection.”

- International Labour Organization, Minimum wage chart: Bangladesh, Cambodia & Viet Nam

- Global Fashion Agenda, Pulse of Fashion Industry, Boston Consulting Group, (March,2019)

- UK Parliament Webpage.

- Deloitte Access Economics for Oxfam Australia, A Living Wage in Australia’s Clothing Supply Chain (2017); Global Fashion Agenda, Pulse of Fashion Industry (2017)

- H&M, H&M Group Sustainability Report (2018)

- The Anker Methodology is a widely accepted and published new methodology to estimate living wages that is both internationally comparable and locally specific. It was developed by living wage

experts Richard Anker (formerly ILO) and Martha Anker (formerly WHO). See the detailed description here - New York University’s Stern Center for Business and Human Rights, Made in Ethiopia: Challenges in the Garment Industry’s New Frontier (2019)

- Eg. Levi Strauss (2018) ‘Project F.L.X. Redefines the Future of How Jeans Are Designed, Made and Sold’